Patient Safety and Health Equity in Vulnerable Patient Populations

Strategies and Best Practices to Improve Outcomes - April 2019

Introduction

Problems, Strategies and Best Practices to Improve Outcomes

Pulse Center for Patient Safety Education & Advocacy is a nonprofit organization dedicated to raising awareness about patient safety through advocacy, education and support. Pulse holds annual symposia focusing on themes related to safety and ways to improve the healthcare system. This year’s theme was Patient Safety and Health Equity in Vulnerable Patient Populations. We brought together providers, caregivers, health care executives and patients to address issues impacting:

- Those with Limited English Proficiency (LEP)

- People living with Alzheimer’s or dementia, and

- Members of the LGBTQ community.

Our goal was to determine what inequities in healthcare delivery exist for these groups and to develop strategies for patients and providers to reduce or avoid them.

Our panel of experts presented practical techniques for improving communication and care in these vulnerable populations, and representatives of the included populations provided personal perspectives. We then engaged in a dialogue designed to respect both experience and expertise, working together to determine what is happening in the healthcare setting and how trust, care and quality can be improved.

We supplemented the conversation at the event by looking at statistics and solutions being used today. The result is a deep dive into problems faced by growing groups of patients, suggesting measures providers and patients can use today, including changes in culture and attitude.

We subsequently conducted additional research, deepening our knowledge base, and using it to evaluate the usefulness of solutions developed at the Symposium.

The Problem

We brought together 50 providers, caregivers and patients to examine obstacles to care for vulnerable populations. While health insurance and economics impact care, we found that cultural insensitivity, implicit bias, misunderstanding, and many other factors negatively impact the experience for these groups, and whether or where they seek care.

These negative factors are at the heart of Pulse’s Healthcare Equality Project, which is an independent, community-based program dedicated to improving the quality and safety of medical care for patients belonging to at-risk groups: ethnic and racial minorities, those who have certain specific diseases, and those belonging to any

vulnerable or discriminated-against community outside the mainstream.

We found that, despite massive investment in healthcare infrastructure, the experiences of vulnerable groups are still too often ignored or sidelined by individual providers and systems. We concluded that this blind spot in the medical rearview mirror provides an immediate opportunity to improve care and, likely, outcomes. Patients can be more effective as partners in their own care, and providers can provide comfort rather than discomfort, inspiring confidence instead of distrust. We believe that this is a matter of will and empathy rather than cost.

The Symposium

The Symposium brought together voices from various constituencies, including patients/families, case managers, social workers, nursing students, providers and health care executives. The event was held in a setting designed to promote honest dialogue. Health care providers summarized their professional knowledge, experience and research. Guest speakers, patients and caregivers told moving stories of their struggles and successes, and made suggestions.

Major participants in the 2019 Pulse CPSEA Symposium were:

Sponsors

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Family First Home Companions

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Nassau-Suffolk Hospital Council, Inc.

Polo Plumbing and Heating LLC

Step Ahead Networking LLC

Sea Star Strategy

Χ Η Φ

Care Answered

Co-Chairs:

- Robin Moulder, Manager of Quality and Safety at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York

- Alyssa Cottone, Operations Manager, Family First Home Companions, Continuing Education Provider and LGBTQ Advocate

Keynote speakers:

Healthcare and related professionals

- Ilene Corina, BCPA, President, Pulse Center for Patient Safety Education & Advocacy and Director of the Healthcare Equality Project

- Laura Giunta, Certified Senior Advisor and Alzheimer’s and Dementia Specialist

- Robin E. Moulder, RN, BSN, MBA, CPHQ Manager of Quality and Safety at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York

- Patrick Samedy, Associate Director of Quality and Safety Systems at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

- Ronald Wyatt, MD Chief Quality Officer at Cook County Health in Chicago, Illinois and Co-chair of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Equity Advisory Group

Healthcare consumers representing patient populations:

- Mirna Cortes-Obers

- Joan Crescitelli

- Kyle Schuessler

Authors of the White Paper

- David Halperin, Director of Communications, Pulse CPSEA

- Claude Solnik, Journalist

Photos

- David Halperin

Support

- Chira Budick

- Diane Hawkins

- Amy Norris Wenzel

- Mary Redler

- Roberta Rosenberg

- Rita Said

Moderators

- Alyssa Cottone

- Beverly R. James, BSN, RN

- Clemencia Solarzano, PharmD

Participants

Marissa Abram

Teresa Aradjan

Aaron Braun

Shani Bynum

Laura Giunta

Joyce Gomolin

Diego Gonzalez-Molina

Javier Gonzolez

David Halperin

Matthew Heiden

Beverly R. James

Melissa Katz

Amy Kirschenblatt

Christy Manso

Laurie Messina

Tim Moriarty

Robin Moulder

Carolyn Ortner

Angela Papalia

Alexis Porcello

Julia Ramirez

Sharon Reichman

Lee Rudin

Naheed Samadi Bahram

Patrick Samedy

Roy Schmitt

Kyle Schuessler

Aria Sitaram

Claude Solnik

Clemencia Solorzano

Ellen Tolle

Ann Vlahos

Ingrid Williams

Ronald Wyatt

A Message From the President About This White Paper

In order to write a white paper, we conducted additional research, deepening our knowledge base, and evaluating the usefulness of solutions developed at the Symposium. This white paper is designed to provide an additional tool to assist providers, patient advocates and the public in improving the crucial partnership between provider and patient.

This white paper is not based exclusively on data, but relies heavily on the experiences of providers, patients and caregivers. We have identified certain issues that impact care in vulnerable populations. In the end, it’s all about one thing: making patients from these populations feel safe. The consequences when patients do not feel safe are very clear and very real. Providers want their patients to be partners, to provide information and follow instructions. People who do not feel respected and treated well typically experience distrust and discomfort. And these have very real consequences in the patient-provider relationship.

In our healthcare system, medical devices are developed and advances occur regularly and rapidly. At the same time, data, perspective, study and analysis of patients’ and providers’ experiences can give us medical tools as essential as scalpels and X-rays. This white paper looks at each of the varied groups we considered, yet brings them together in one study, identifying common and separate issues and solutions regarding inequities in healthcare delivery to these groups, and strategies for reducing or avoiding them.

Basic Conclusions

Unconscious bias, stereotypes and assumptions negatively impact both comfort and care, although in various ways for various groups. While providers must treat disease, it became clear to us that it is crucial to be sensitive to the culture and characteristics of the individual as well, in order to treat disease effectively. Treatment at its best is a partnership between provider and patient. We also found that people from these groups are sometimes not communicative, which compounds diagnostic and treatment issues. We believe that people seeking medical care must look at themselves not as passive recipients of treatment, but as partners in care. Provider behaviors that alienate or stimulate distrust may result in patients failing to follow through, return for follow up, or disclose information necessary to treat. At the same time, patients’ reluctance to reveal their stories may damage their own care.

One must know the disease, but also know the person. This is crucial in an era when so little time is available to spend with each one. As interactions with providers become episodic, the relationship between provider and patient becomes increasingly tenuous, making it even more essential to develop procedures and practices that allow providers to get to know patients as soon as possible after intake. We found that, in many cases, the healthcare system — from medical school to bedside — does not foster or integrate an awareness of the culture and expectations of each group. And we found numerous ways that cultural competency can be improved, enhancing care and outcomes at little or no additional cost.

Prejudice and miscommunication were experienced by all three groups represented at the Symposium regardless of the health care professional’s training level. We found emergency room patients with dementia being asked questions, even though their answers often were unreliable. We found LGBTQ patients often ill at ease due to insensitive language, lack of privacy in the emergency room, and difficult questions or requests in doctors’ offices. We found patients with limited English proficiency often disguising their limitation, while providers wrongly, if conveniently, believe they understood instructions. All of these are opportunities to improve.

Based on our findings, we asked participants to make suggestions as to how to improve care, put patients at ease, and identify and eliminate bias that is often unconscious. Highly engaged participation in breakout groups yielded numerous suggestions and solutions. Information gathered at intake, we concluded, is best when it includes information about “who the patient is” as well as about his or her illness. And unconscious, implicit bias among providers needs to be addressed in order to avert errors that can negatively impact medical care and the individual’s willingness to disclose personal details and follow through with care. We supplemented the conversation at the event by looking at statistics and solutions being used today. The result is a deep dive into problems faced by growing groups of patients, suggesting measures providers and patients can use today, including changes in culture and attitude. While healthcare systems must address and make advances in medicine, cultural issues — if not addressed — can stand as barricades on the road to good care. We believe that the first step to solving these problems is an awareness of where and when they exist. We have assembled steps that can serve as benchmarks and best practices from doctors’ offices to emergency rooms.

Common Inequities

We found that those with Limited English Proficiency (LEP), people living with Alzheimer’s or dementia and members of the LGBTQ community each face their own specific obstacles, but also face similar problems. Many people interacting with the healthcare system feel vulnerable, which can interfere with and impact their willingness and even ability to seek care. We also identified numerous ways that patients were marginalized during intake, or made to feel marginalized. When people feel marginalized, we must deal with that as a reality, even if it is not deliberate. The distrust that follows is very real and detrimental. Trust is the first tool a provider needs in order to treat.

As patient safety is addressed or studied by medical professionals and healthcare systems, the patients’ and families’ voices are often not included in care quality improvement strategies. Providers, swamped with medical information, can experience a lack of empathy with the people they treat, as facts overwhelm feelings. In this white paper we seek to combine facts and feelings, experience and expertise. We found that by bringing people with similar experiences together, we can develop strategies that will work for various groups. The diseases or direct complications related to each population do not have to be identical, but the circumstances are related. Improving care for a person who is transgender can help someone who cares for an elderly parent with Alzheimer's. We have heard the voices of providers, patients and caregivers and have combined them in a way that we hope can convey messages that, can be used to improve care.

Ilene Corina, BCPA

President of Pulse CPSEA

[email protected].

(516) 579-4711

“We keep talking about disparities. We keep doing the same thing over and over again. Stop counting the disparities and do something about it.”

- Dr. Ronald Wyatt

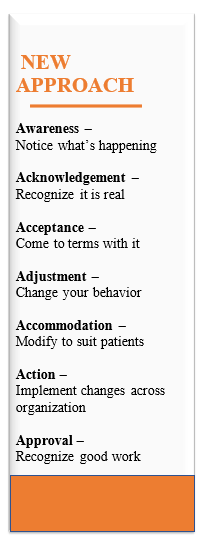

A Model for Improvement

The best way to solve a problem sometimes is to find how other problems have been solved. In order to solve the problem of inequity, we looked for other healthcare issues where there has been progress. And we determined there are certain parallels and lessons learned that can help address these.

A growing awareness, the first step in solving a problem, has led to increased action. In keeping with this approach, we will produce and provide a checklist of key measures and best practices designed to reduce or eliminate inequity, increase comfort and improve results. Institutions can even use this as a scorecard to see where they stand and what they can do.

Our intention is to develop suggestions and best practices that can serve as a tool kit to improve care for vulnerable populations.

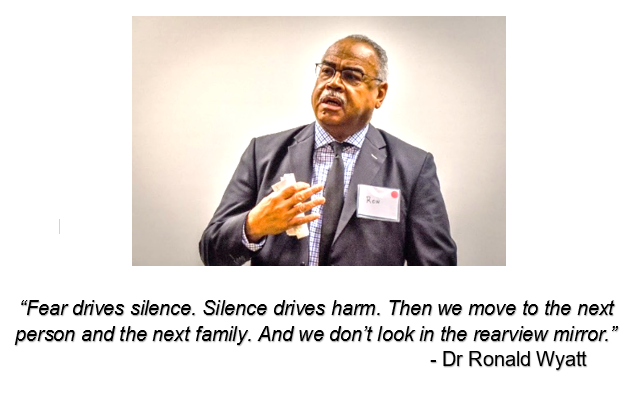

At the symposium, experts, patients and caregivers all discussed examples of disparities, implicit and even explicit. Disparities may appear to be built into the system. “We keep talking about disparities. We keep doing the same thing over and over again,” says Dr. Wyatt. “Stop counting the disparities and do something about it.”

He indicated that improving the way vulnerable populations are treated could significantly improve care. This could, in effect, change the world of healthcare for some.

“When you say, ‘Change the world,’ people are like ‘Whoa!’” Wyatt said at the symposium. “But that’s what we’re talking about. This is urgent. In order to change the world, though, you have to change the ground you stand on first. Look at the ground you stand on and change it.” Wyatt says providers need to make patients feel secure and at ease. If they focus on the science and not the human, knowledge and not compassion, providers can intimidate their patients, which is not helpful in fighting illness.

“Fear drives silence. Silence drives harm,” Wyatt says. “Then we move to the next person and the next family. And we don’t look in the rear view mirror.”

Data Drought

We live in an era of big data. Healthcare systems collect and provide huge amounts of data to government. Electronic medical records make it easier than ever to move information. And yet, when it comes to patient populations such as LEP (Limited English Proficiency), LGBTQ and (to an extent) those with dementia, we often have a black hole more than a big book.

In other words, we don’t necessarily have data about many vulnerable populations. Part of this is policy and procedure. Part of it is simply practice. If we can’t even ask the right questions, it becomes even more difficult to get the answers.

Hospitals don’t have much data regarding sexual orientation, even though this can be crucial to care.

“Even data for hospitals,” Wyatt says. “Hospitals still haven’t figured out how to accurately collect information, to ask the right questions the right way to capture the right data.”

And some things designed to be good have a downside. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, for instance, was designed to protect privacy. But HIPAA – even if misunderstood – can lead to barriers and lack of information for caregivers. And a focus on privacy is leading to problems in getting medical information promptly.

“Once you have good data, you can do interesting and cool things with the information,” Patrick Samedy says.

Technology provides more data but increases the distance between people and providers. But providers need to collect more data about vulnerable populations both from patients and providers.

“We motivate our staff to share information and insights with us through an efficient reporting system,” Samedy says, regarding information solicited from staff.

It’s possible to get feedback through informal channels, however, about what’s being done well and what isn’t.

“The data is out here and it’s easily accessible,” Samedy continues. “They tell us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. It’s up to us to take the time to listen and motivate change.”

Dishonesty at the Doctor’s

While comfort is a core value at providers, it’s important to realize that “discomfort” has costs far beyond lower Press Ganey scores. Dishonesty makes good care difficult, if not impossible. Honesty is possibly the most important tool that providers can get from patients. Honesty is crucial to solving any problem. To be honest, one must know and say the truth, a problem among those with dementia, certainly. But dishonesty in the doctor’s office is a serious, if often overlooked, problem.

At the symposium, there was an effort to help people feel safe, so they could be honest. People were told that breakout groups were designed to be safe zones, with participants seated in circles facing each other. Leaders were chosen carefully, as moderators with good management skills. It was made clear that others in the group were members of these vulnerable groups, and that the day’s goal was to find the truth and if possible, to identify strategies to make care better. In addition, people were told they could remain anonymous in the white paper, unless they wanted to be identified. In these circumstances conducive to comfort, people spoke out, often from the heart, about times that they lied to their providers.

NOTE: the names of some speakers in the stories that follow have been changed to respect their privacy.

Privacy and confidentiality are key elements in obtaining honesty. We focused on situations where people dissembled, both in healthcare and other settings. We found that when someone is worried about a negative consequence, they may dissemble to protect themselves from perceived harm. A nursing student from El Salvador said he told people (although not providers) that he was Puerto Rican, due to concerns that some people associated with his nation were gang members. Lying can pose obstacles to solving any problem. But situations that lead to lies in intake can pose particularly significant problems.

“I think about my grandparents,” one person says of situations where lying became a survival strategy. “When my grandfather came over here, he totally had to hide who he was. He wouldn’t join organized crime. His business was ruined by the mafia several times. He was looked down upon by the Irish immigrants. It was a generational thing. I haven’t had to hide my identity.”

For healthcare providers to treat people properly, they have to know what’s happening. When someone brings a car in to be fixed, they may be asked if there are sounds or other “symptoms.” When a provider asks questions, the answers are key data used to at least begin making a diagnosis. Lying can send a provider on a wild good chase, at least at the start.

Biases, prejudices and simple lack of sensitivity often interfere with the flow of information. Patients with limited English proficiency, dementia, or Alzheimer’s, and LGBTQ patients, sometimes seek to disguise these attributes. If they are uncomfortable, they may not disclose information, impacting care.

Someone with limited English proficiency who seeks to disguise that fact, for instance, may not understand important information or instructions impacting medications or other medical care. They will, however, indicate they do understand, out of a desire to appear competent. And they may not understand what they do not understand, unaware they are missing key instructions for care. Clemencia, a pharmacist and breakout facilitator explained: even though there so many people in this country who are not English speakers, “there’s a certain amount embarrassment about it. They don’t want you to know that they don’t understand what you’re telling them. And the conversation can get very weird because you’re asking a question, and you’re not sure if they’re understanding.”

LGBTQ patients may not disclose their sexual- or gender-orientation to providers who don’t already know. Someone who is injured or sick, for instance, could conceal information that would help treat them. One transgender woman explained a recent

situation on: “I was in the hospital for one day not too long ago. I was trying to get a point across to the person who was intaking me, a nurse practitioner, I guess that’s what she was. The point wasn’t getting across. She wasn’t using the right pronouns. So I corrected her and corrected her. I didn’t know what else to do while I was there. I was kind of reluctant to make too big of a scene, because I was trying to get an operation done in another hour. So I didn’t want to get myself crazy, I didn’t want to cause that much more stress for myself. But it was stressful.”

situation on: “I was in the hospital for one day not too long ago. I was trying to get a point across to the person who was intaking me, a nurse practitioner, I guess that’s what she was. The point wasn’t getting across. She wasn’t using the right pronouns. So I corrected her and corrected her. I didn’t know what else to do while I was there. I was kind of reluctant to make too big of a scene, because I was trying to get an operation done in another hour. So I didn’t want to get myself crazy, I didn’t want to cause that much more stress for myself. But it was stressful.”

And undocumented immigrants sometimes simply do not seek care, creating a separate problem and sometimes even leading to higher costs for care down the line. They are concerned about consequences related to discovery of their immigration status.

It is crucial that providers, through both overt and indirect signals, make it clear that honesty will not be punished – and that they don’t have prejudices. Otherwise, patients will steer clear of truth, which can impact care and lead to higher mortality rates.

The Fear Factor

Paula, a lesbian who grew up in the 1960s, remembers moving to Arizona with her partner. She loved the landscape and the location, but she was concerned. “This is 20 years ago. We had to sit down with the realtor and say, “Where will it be safe for us to live?” she says. “We weren’t in Flagstaff or Tucson. We had to trust that person would steer us. We never had any incident or problem. It’s something a lot of people don’t have to think about.”

Times have changed, but prejudice against LGBTQ individuals still exists. And for Paula, fear hovers over many decisions. She remembers growing up in a society where sexual orientation was not openly discussed or dealt with in an even-handed way.

“I am a product of my generation. In the Sixties, you didn’t come out to your Roman-Catholic-go-to-church-every-Sunday family,” she says. “And you didn’t come out at work. You were concerned. Maybe I carry some of that. That’s my baggage.”

When people interact with the healthcare system, fear is frequently an element. But for vulnerable populations, it is often a component of other interactions even before they see a provider. It’s important for providers to be sensitive to that presence, that past and that experience.

“It’s not easy to come out from fear of discrimination and rejection,” says Laura Giunta. “Some are surprised by acceptance.”

Patients do best when they realize fear can prevent them from being treated properly. Fear can lead to silence, dissembling and simply not disclosing. People may have to overcome their reticence in order to serve their best interests. If silence can be a survival strategy — Don’t ask, don’t tell — it can be anything but that in a doctor’s office or a hospital.

Fear can have a high cost in care – financially and otherwise. LGBTQ individuals, for instance, are less likely than heterosexuals to reach out to providers, because they fear sexual orientation- or gender-based discrimination and harassment, according to Alyssa Cottone. Fear of embarrassment also can be a powerful motivator.

“It’s always scary for me,” Paula continues, “if I have to identify as a lesbian no matter where I am.”

She says this is particularly true with a doctor she does not know, because of the physical element and lack of privacy.

“It’s too bad we can’t get medical providers to identify themselves on their websites as gay-friendly,” she says. “Or whatever terminology they might want to use.”

Some providers are beginning to identify as gay-friendly, but the larger issue is establishing procedures to provide comfort and care. Providers need to make it clear that they will provide care without prejudice. In some cases, a statement welcoming a particular group can go a long way toward doing that.

[On forms] “They ask the name, phone number and relationship. I always wrote ‘partner’,” says Paula, who attends a gay-friendly church so she knows how to find support. “I didn’t want to not be who I was. By the same token, I wondered how that was reviewed. Whoever looked at it, whether it’s the medical assistant, the nurse or the doctor. I remember always hesitating to fill that line in.”

As she sees it, good care goes beyond good procedures to a cultural competence that means caring for all. But practitioners also need to know how to be sensitive or, inadvertently, they can offend their patients.

“I know an OB/GYN seeing a lot of transgender people,” she says. “No-one says how to be sensitive to people who come in.”

During the breakout session, Laura Giunta shared her personal experience as a daughter of a parent with dementia. “My mom is 67. She is slipping quickly. I know, just from doing what I do, that it's dementia, I believe it's vascular. So she sees that certain things are not what they were, and what she's been doing now is refusing to go out. She doesn't want to be seen, she doesn't want to go to anything. We had a family shower. She broke down. She didn't want to come to it. She's afraid because anything that comes out may give this away, and she's not ready for that yet, for anyone to know that anything is wrong. So she's lying and hiding and isolating, and all of those things are going on.”

Dr. Wyatt says providers need to make patients feel secure and at ease. If they focus on the science and not the human, knowledge and not compassion, providers can intimidate — which is not helpful in fighting illness.

Cultural Barriers

Race, sexual-orientation and language are just a few cases where health providers sometimes fall short. Cultural ignorance and insensitivity also are taking their toll.

Some cultures are male-dominant, Wyatt says, “so everything you’re doing, you need to include the male family member.” In well-documented cases, “The male person wouldn’t allow the woman’s follow-up appointment. They wouldn’t allow the prescription to be filled.” When providers included the men in the process, they achieved better results.

People in various regions — for example African-Americans in the South — sometimes have local terms or phrases not used elsewhere. When providers were unaware of those, a communication gulf resulted. The provider would say one thing, while the patient would hear something else, and vice-versa.

Imogen, a registered nurse, remembers a patient from British Guyana who had trouble communicating with staff. “To effectively treat him, you needed a true picture of his home environment,” she says. “He was a very sick, elderly gentleman.”

She said in order to care for him, the hospital needed to be able to talk with him, involve family and get feedback. Other providers eventually took her advice and called his son, who pierced the language and cultural barriers. Imogen told the son to advocate for his father and help with after care and follow up.

“I thought about all the patients who come in who don’t have anybody by their bedside and can’t communicate,” she said.

We must note that there are differing views about who is the most appropriate translator. Some experts believe that trained professional translators are more likely to convey accurate information in both directions than family members. However, a family member may be the only one available in some cases, which could be problematic. See the “Breaking Through the Language Barrier” and “English Not Spoken” sections below.

It’s important to realize that language and culture often go together. There may be cases where we’re sensitive to one issue, without recognizing the other. Diego, the nursing student, works on a hospital floor that includes patients who speak Spanish.

“I tend to speak to them in Spanish and build rapport,” Diego says, noting that language, culture and comfort dovetail.

Privacy as a Factor in Cultural Competency

One hospital uses interpreters over the phone via video, showing them on screen. But those aren’t always available. A nursing student remembers a physician asking him to translate.

“A physician was in a rush,” Diego says. “This patient needed the interpreter badly. He would smile, but he would never answer correctly.”

The patient, who had not been educated past the second grade in El Salvador, wasn’t able to understand or communicate with the physician. So Diego stepped up.

“The doctor said, ‘Diego, come here. I need you to translate things in Spanish,’” Diego says. “The patient’s brother was there.”

The patient had said he did not want his family to know the results of an HIV test the doctor ran. But Diego knew the brother would understand anything he said in Spanish.

“The doctor says, ‘Oh and tell him he’s HIV positive,’” Diego says. “As soon as he said that, I stopped speaking. He said, ‘Why did you stop speaking?” I said, “Can I talk to you?”

They stood in the hall where the doctor asked what the issue was. Why wasn’t Diego translating? “You know I can’t do that,” Diego says he replied. “I know what the patient’s preferences are. The doctor acted like I inconvenienced him.”

One participant who was 22 at the time gave evasive answers to a provider in a hospital emergency room, because her mother was present.

“I said you shouldn’t have asked those in front of my mother. And let me give you the right answers,” she says of her conversation with the provider later. “At least I was honest. I realized I had to be the advocate for myself at that point.”

Healthcare systems provide cultural competency modules. Wyatt says that training can provide confidence in competency, but not necessarily the real thing. Providers need to be sensitive to privacy and other factors regarding setting.

Humility in Healthcare

Cultural competency isn’t just about training, but about people. It has to do with the way human beings treat human beings. Providers can become proud of cultural competency, rather than using it to be more compassionate.

“Chinua Ashebe said, ‘You can’t come into my house through your gate. I have to invite you in,’” Wyatt says. “We think we can become culturally competent. We can walk up to anyone and say, ‘Let me tell you about you. Let me tell you about what you believe.’”

Cultural competency involves an attitude and partnership with proactive patients. It is about the “customer”, not the provider.

“We can co-produce better health if we understand each other,” Wyatt says.

Wyatt says cultural humility can help build trust. Physicians who become too paternalistic create a “power distance” between themselves and their patients. Cultural humility leads to respect for different cultures.

“That helps to close the gap. Not just today. But for the rest of your life. If you cannot be humble in healthcare, I urge you to find something else to do,” Wyatt says. “Cultural humility is a lifelong process. Every day, to this day, I ask myself, ‘Did I say that the right way? Did I understand what I was being told? Did my body posture say something different? Were they the right words spoken the right way at the right time?’ I reflect every day on what happened today. That can make me a more humble person tomorrow.”

We can change the world. Each person is a world and not just a waystation in a provider’s daily journey. Providers can lose track and lose sight of patients’ humanity as people become cases. A patient is a person, not a problem. Wyatt talks about a gay black man and lifelong family friend who sang on Broadway in Porgy and Bess, married a lesbian, because it was easier to get work if you were married and looking for work in New York City in the 1960s.

“They figured he best way they could get work was to appear to be a married couple,” Wyatt says. “They felt more respected if they portrayed themselves as a married couple.”

After the man became sick and needed to have a heart valve replaced, he went back to Birmingham, Ala., for surgery. And he became an HIV advocate in Huntsville, Ala. One day, Wyatt got a call from the patient’s brother who said he had 105-degree temperature. The treating doctor had not called Wyatt, even though he was the man’s physician. At the hospital, Dr. Wyatt reviewed the chart and concluded that the doctor placed little value on this man’s life.

“The Darth Vaders in medicine,” he says of this doctor. “The first line in the history was ‘disheveled, ill-kept, malodorous black man.’”

This man had sung on Broadway, entertained many thousands and then been an advocate. He had lived a life at once heroic and tragic. But a doctor had dismissed the man’s entire life, including the man’s humanity, in a few lines. Instead of feeling and showing respect, he judged him by his appearance when he arrived, sick, in the hospital. Knowledge of medicine is no guarantee that a person will not be ignorant of a patient’s life and humanity.

“In those few words, he was saying, ‘I don’t respect you. As far as I’m concerned, you have no dignity and I have no compassion for you,” Wyatt says. “Therefore, you can just die.”

Wyatt called the man’s brother and told him he needed to get to the hospital asap. When he arrived, the attending physician said they should let the patient die. But when the patient’s brother identified himself as a physician who was the chair of gynecology at a hospital, the attending physician immediately changed his tone and behavior. The brother threatened to go to higher-ranking doctors, if this provider did not do what he could to save the man’s life.

“Why does he or she act that way? Is he or she afraid of something?” Wyatt asks.

A good physician is not simply one with knowledge. It is one with compassion. It is easy to stop caring. And when you stop caring, you might as well stop providing healthcare.

“Our part is to care,” Wyatt says. “Our part is to show compassion. Our part is to respect people.”

Wyatt says that it’s important not simply to root out the inhumanity from healthcare. Systems need to structure themselves, to teach themselves, not to be inhumane, to value each individual, regardless of income, religion, race or other attributes. When we identify an individual error, it is an opportunity to prevent it from repeating. Noticing an error is not repeating it, but rather an opportunity to help others not repeat it.

To illustrate why we need to look upstream at the social determinants of health, Dr. Wyatt told this story: “Someone drives home after a hard day of work and sees people rushing down an embankment. He goes down to see what’s happening and sees people pulling babies out of the water. He turns and walks away,” Wyatt says. “Someone says they need him: they have to get the babies out of the water. Why are you leaving? He says, ‘I’m leaving because someone keeps throwing the babies in the water. We need to stop them. Someone on the bridge is throwing people in the water.’”

Wyatt says it’s important not to simply address an individual incident, but to identify underlying causes to prevent ongoing harm. It’s important to make sure that systems value cultural humility and show respect, empathy and compassion.

“We spend a lot of time downstream, deciding whether or not we’re going to put pieces back together,” Wyatt says. “We must go upstream.”

Patrick Samedy

Providers from Vulnerable Populations

While we have focused largely on patients from vulnerable populations, providers also may be part of these groups or observe the prejudice those groups face. And healthcare systems ideally should be sensitive to them, as well as to patients. Providers may come to the job after experiencing or seeing prejudice outside the health system. ≈ Patrick Samedy moved to Long Island as a teenager in the 1980s and as a young man faced pressures due to his heritage.

“The grit and the hard work that my family had to endure to get us here and get me where I’m at today, I’m extremely proud of where I am today,” he says. “I wish I leveraged that a little better at a younger age.”

Other providers talk about seeing prejudice in action. Diego says there’s a stereotype that comes with being Salvadoran where he lives, “especially a Salvadoran young male.” “The first time, I said ‘Salvadoran’,” Diego says. “I got statements like, ‘Do you have family members who are gang bangers? Have you had a violent family at home?’ I even thought I’d be judged.”

When Diego was in a setting with nurses, he was asked what kind of Hispanic he was. “I am an American,” he says he replied. “But my blood is Salvadoran.”

Diego says his own support system has always been fairly limited, in part because his family immigrated. He has seen many people who are intolerant and prejudiced, but that hasn’t influenced him.

“I don’t have Christmas like that or huge Thanksgivings,” Diego, whose family is primarily in El Salvador, says. “Just me and my mom. My support system is my own mental clarity.”

Imogen, a registered nurse originally from India, remembers when her husband, a doctor from Haiti, got sick. “At the time he got ill, he was in his sweats,” she says. “He had to go to the hospital. He wasn’t dressed appropriately.”

Her husband was a physician and she was a nurse. But once they arrived at the hospital, they were members of a minority, and not the medical one, in the eyes of hospital staff.

“They thought I was his home health attendant,” she says. “We’re not the same nationality, so they assumed I was not his spouse.”

They never told the providers that she was a registered nurse or that he was a physician. While this was hardly an experiment, it would yield evidence of a failing system.

“They came in. They spoke to him as if he was illiterate. They were very disrespectful,” she says. “My husband said nothing. The physician told him that ‘If you don’t do what I tell you, you will be dead in x amount of time.’”

Her husband told this doctor that he was off the case: The patient, a physician, felt he was being treated poorly and without respect. “The physician left and did apologize. He had no idea what the patient did. He judged him by race and the way he was dressed,” Imogen says. “He assumed the person near him was not his wife. There were too many assumptions that were made.”

Support Networks

In network” and “out of network” may be common terms in healthcare, but another kind of networks — support networks — are a crucial element in obtaining and following up with care. It’s important for every patient to have a support network – and for providers to understand what that network is and isn’t. Vulnerable populations may have support networks, but they can be different from typical ones. A transgender man asked about his family gives a brief answer.

“He said, ‘I don’t have a family,” a provider reports. “When they found out he was transgender, they didn’t want anything to do with him.”

His mother, however, accepted him. His support network became fellow workers. “Some of them don’t come out,” a provider says of transgender patients. “They don’t want the family to know.”

LGBTQ people sometimes experience rejection because of sexual orientation. At age 17, Diego, now a nursing student at a local Long Island university, knew a Hispanic girl who wanted to go to the prom with another girl.

“Her parents would never allow that. My friend wanted me to take prom pictures in front of her parents,” Diego says. “I would leave and her partner would come and she would switch into the limo.”

The girl’s mother found out about the plan and Diego’s participation in it. “My mother got a phone call saying, ‘Your son is supporting that, because he’s too American,’” Diego says. “’He grew up too easy, had clothes, shoes. You should send him to El Salvador.’”

David, a former nursing home administrator, says people with dementia often become isolated from, if they don’t entirely lose, their support network. “Working with people with dementia has been a particular challenge,” he says. “Like many populations, they are separated and removed from society. Typically, communities aren’t comfortable with somebody with dementia.”

David has been caring for someone with dementia for several years. There is a temptation to further isolate the person. David believes that’s not healthy.

“We always take him out into the community,” David says. “We stay active. Every opportunity we have, we take it. Part of desensitizing people is making it familiar, comfortable. Making it a daily part of activity and involvement, caring and sharing with other people. As opposed to isolation and separating and keeping them apart from other people.”

It’s also important to realize that spouses and caregivers can feel alone. “They become isolated they lose their network, their support,” David says. “They lose their ability to go out in public for typical activities.”

David says he works with a woman who is — and is married to — a neurologist, although her husband has dementia. David says that she committed to continuing to live their life despite fact that her husband has dementia. She takes him to conferences, shows and plays.

“We’ve gone through the different challenges and shared how people react,” David says. “The more she does it, the more comfortable people become, and the more engaged they become. When people become engaged, they learn and grow. Their perspective changes.”

While it’s probably easier to leave people in isolation, David doesn’t believe it’s better. Providers and other members of the public may suggest removing a person with dementia from the rest of the world. But that, if not pure prejudice, may be a case of the system actually chipping away at the support network.

“It takes courage to stand up to all of the people who have more power,” David says.

Misunderstanding Medicine

Language in healthcare often goes well beyond the language spoken, showing how important communication is. Providers in a hurry often use acronyms to save time. Still, acronyms create problems in healthcare. A patient at an urgent care center is told he can leave “AMA” – against medical advice, but only the acronym is used. Acronyms create a language that providers use, a special code that shows how professional they are, giving them the authority that goes with being above others. Acronyms are a private language that breeds misunderstanding, which in turn is likely to breed not simply disrespect but, at some point, distrust. When addressed to the patient, jargon also pushes the that person away. Nothing is easier to understand than the prevalence of misunderstanding in medicine. A patient is told a provider is going to take her vitals. She becomes afraid, not sure what is being “taken” or what that means.

“She thought I was going to take something vital,” says Robin Moulder, Manager of the Division of Quality and Safety at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and conference Co-Chair. “She thought I was going to rip her heart out.” In another case, a patient’s caregiver says the patient no longer wants a nurse to visit. Then the nurse finds out why.

“’Look at what that nurse wrote about my husband,” a woman tells a provider. “’Patient is SOB.’ She didn’t know that meant Short of Breath. Once I explained it to her, she had the grace to laugh.”

Misunderstanding may be the most overlooked form of medical error, yet it may be the most common and most easily undetected. But language and communication are as important as a scalpel and MRI. A doctor spoke quickly, when explaining how to use an insulin pen. The patient didn’t hit the plunger, so the woman’s sugar went up because the pen didn’t work.

“She said the doctor talked so fast, “a symposium participant said of her mother. “She didn’t see her hit the plunger.”

Inaccurate, incomplete or simply misunderstood instructions show the importance of language. The caregiver for someone using a fentanyl patch for pain control was told to change the patch every 72 hours. The caregiver simply added a new patch, without removing the old ones.

“The on-call nurse gets a call. ‘I can’t wake my father up,’” a provider at the conference says. “He was covered in patches. There was a learning experience for that nurse.”

Language brings connotations with it. Imogen, a registered nurse, believes calling a patient “non-compliant” can miss the point. The patient may have problems with the plan of care, which can open up new dialogue or even new options that will lead to follow-through.

“You do not assume someone is non-compliant because they are not adhering to your plan of care,” she says. “If you tell me to do something and I don’t agree with it, I won’t do it.”

Healthcare provided in a hurry is often healthcare in which the patient becomes confused, itself a condition that can impact care. We need to understand that communication must be a core value. And we need to be able to stop, slow down and repeat when it appears that communication may not be clear.

At the same time, patients also benefit from understanding their role. When a provider spews a long stream of information, that leads to confusion. Everyone should feel safe indicating they do not understand. Ignorance is a condition easily remedied. Yes, this may slow the process at the moment, but can avert errors or confusion later on.

Dementia and Alzheimer’s

Dementia is at once a growing problem and one increasingly being treated. We are taking steps to reduce it through medications. Our arsenal of drugs has grown varied and sometimes effective. And with this, we are beating back dementia more than in the past.

In the United States, there is a desire to be treated equally. But the fact is, we also need care to reflect condition. As the population ages, the number of people with dementia and Alzheimer’s is growing, which requires a system to acknowledge, accommodate and be accountable. This also means a growing number of caregivers, and a need for providers to understand how to handle intake and treat other conditions for people with dementia. That means including caregivers in the process when we admit and treat patients with dementia. Instead, many caregivers are sometimes marginalized or ignored while people with dementia, unreliable narrators, are interviewed.

Ron Wyatt used to call Molly, his great-aunt in Alabama, once a week. One day he got a call that “something was wrong” with her.

“Molly had dementia,” Wyatt says of the way the disease arrives. “The person who taught me.”

“Molly had dementia,” Wyatt says of the way the disease arrives. “The person who taught me.”

Dementia can change people, including their ability to absorb and process information. We need to alter our way of interacting. Providers must acknowledge that — appearances aside — decisions made by someone with dementia can be pliable and change dramatically in an instant. Joan Crescitelli, a caregiver, tells a story of taking her 86-year-old mother, diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s, to the emergency room where she was tested and eventually given a diagnosis of congestive heart failure. Her mother clearly needed continued care, but did not absorb information about the severity of her heart condition.

“So here we are in the ER and my mom starts to chant her mantra, ‘Why are they so slow? I want to go home, I don’t want to be here,’” Crescitelli says. “These few words are repeated each and every time a healthcare provider speaks with her.”

The providers hear this loud and clear, but they do not, she believes, hear another important fact: all information is being filtered through dementia. She says she could see clearly that her mother “cannot breathe and that she needs to be here in the ER.” And yet providers ignored the dementia diagnosis and the caregiver, as they continued to ask the patient what she would like to do.

“Each time a new healthcare professional came in to speak to my mom, I took them off to the side and informed them of her Alzheimer’s diagnosis,” Crescitelli says. “I wanted my mom to be treated with respect, but it was imperative that the provider knew that her answers would be incorrect.”

Providers continued asking the patient for information as part of intake, while not seeking information from the caregiver.

“As I respectfully chime in after each question ‘I take care of her meds’ and I produce a spreadsheet containing the meds and the dispensing dosages and times, I am ignored and informed that they have to ask her,” Crescitelli reports.

With her mother facing congestive heart failure and atrial fibrillation, Crescitelli is convinced that her mother must stay in the hospital. She is concerned about her mother’s health, even if her mother resists staying. Crescitelli is focused on what is right, not what the person wants right now. To her mother, comfort and ease are crucial. To Crescitelli, this decision has implications relating to life and death.

“They need to keep her overnight to regulate her heart and rule out clots,” she says. “These results are being delivered by a doctor in pristine white coat. My mom is now confused, scared and repeats her mantra, ‘I want to go home, I don’t like hospitals.’”

Crescitelli knows that her mother must stay, and yet her mother is questioned to see whether she would like to, or agree to, stay. There is, she says, no recognition that the will of someone with dementia is different from others’ and frequently more like rubber than metal.

“I informed the doctor that there is no discussion…she is staying,” Crescitelli says. “The doctor then adds that, ‘In this country we don’t keep people against their will.’”

Crescitelli, who is her mother’s healthcare proxy and has power of attorney (although it’s not clear as to which variation of this she has), becomes concerned that the providers will honor her mother’s will and whim, even if it is against her own interest. She will be let go “AMA” – “Against Medical Advice.” In this case, finally, a provider arrives who will treat the patient with dementia in a way that would protect her, radiating both authority and respect.

“When the medical doctor who would oversee her care after she is admitted came in, she addressed my mom directly,” Crescitelli says. “She informed her that she understood she didn’t want to stay, but she had to. She spoke with her in a respectful way but with authority, the way you would speak to a toddler.”

This provider followed a protocol that makes sense for someone with dementia. She validated the person’s concerns, but then indicated from a position of authority what actions must be taken. The other providers had not made distinctions based on dementia, but followed their procedure, rather than pursued the patient’s interest. They treated the problem, without regard to the patient, creating new problems along the way. When a provider finally understood the patient’s condition and best interest, it opened the door to better care.

“My mom acquiesced and agreed to stay as long as I would be back first thing in the morning to take her home,” Crescitelli says. “Finally, a little peace.”

Crescitelli and her mother experienced a similar situation on March 8th, 2019, for a scheduled test with her cardiologist. The caregiver repeatedly told providers that her mother couldn’t give accurate information about medicine, although she would answer questions. Providers continued to collect information from the patient.

“I find someone and inform them that she will not be able to answer many questions correctly because her timeline is off. The staff member looks at me and asks me why I didn’t say anything,” Crescitelli says. “I have continuously informed them.”

Laura Giunta believes that implementing a policy of completely informing a patient with dementia can be complex. The person does not process the information the way they would without the disease.

“It comes from the healthcare worker respecting the patient,” Giunta says. “I have to tell my patients everything, because I have to respect them.”

The principal of disclosure takes on a different meaning when the person receiving information isn’t able to process it.

“They don’t have the understanding as a healthcare professional that the person they’re speaking to cannot comprehend,” Giunta adds. “It’s a capacity issue.”

A person with dementia may be overwhelmed and even feel assaulted by a battery of questions they are unable to answer.

“They may not even know the loved one taking care of them,” Giunta observes. “They’re out of an environment they understand. And now we ask them questions.”

It is crucial to understand that a caregiver can be a reliable source of information for someone with dementia, although providers also must realize there can be built-in bias as well. It is, then, important for providers to treat those with dementia differently to other patients. There needs to be a separate protocol, not a situation where providers treat each problem as if it never occurred before. Providers need to integrate caregiver feedback and information or risk getting unreliable information and someone who will refuse treatment.

“I do not pretend to know the answers, but I would like my mom treated with respect and I would like my position as a care giver to be recognized,” Crescitelli concludes. “I explain to her that she is experiencing the aging process. It would be wonderful if the medical community could treat her the same way rather than creating a mess which I am left to clean up.”

When Healthcare Hurts

While interacting with someone who has dementia and ignoring a caregiver may not lead to unhealthy consequences, it can. “Nurses are taught we need to orient our patients,” says Laura Giunta. “But a person with dementia does not base their thoughts on reality. We’re taught to orient them toward reality. Can that be done? No.”

Sometimes interacting with someone who has dementia, seeking to obtain information, can go awry. Giunta, for instance, remembers her 6-foot-2-inch-tall grandfather with dementia being in a hospital.

“All types of things are going on in his mind,” she says. “Orienting him to reality would not be helpful.”

When it was time to leave the hospital, he insisted he is going home and not to rehabilitation. A nurse said that wasn’t possible. “He said he would try to punch her in the face,” Giunta says. “She said, ‘Try it.’ She would punch him back. What did he do? He punched her. Not in the face. But he gave her one.”

That resulted in a report indicating that the patient was violent and combative and had punched a healthcare worker. “Now he couldn’t go to the rehab we picked out for him,” Giunta says. “He had to go somewhere else. He punched someone, so he can’t be helped. That created a downward spiral that led to his death. That did not have to happen at that time. It happened because a medical professional did not take their cues from the person who knew how to handle that individual.”

While the provider’s promise to punch the grandfather back may have been meant as bravado and humor, the patient didn’t take it that way. The provider had taken someone removed from reality and made things worse. A provider may turn to humor to lighten their load, but with someone who has dementia, that statement is likely to be taken literally. Humor can come across as aggression to someone with dementia. There was no last laugh, in the case of the nurse who said she would punch back. A small interaction can set off a series of events with big consequences. Our language can make things better, but when used improperly, can cause damage.

Dealing with Dementia

People with dementia are almost by definition more sensitive than most others. They can be easily overwhelmed and can easily interpret many actions as aggression. Giunta says when a provider stands close or above them, people with dementia become particularly uncomfortable.

“If I say “Hello,’ I want to make sure you can swing your arm and I can swing mine,” Giunta says. “That’s the space.”

Providers may even want to go down on their knees, if a person with dementia is seated.

“You want to be eye to eye. That’s a first line of defense,” Giunta adds. “You don’t want somebody to feel threatened.”

Providers also may do best to stand slightly to the side, so the person has easy egress and can walk away comfortably. “That in itself can help solve a lot of problems, because you’re not upsetting somebody in the first three seconds of meeting them,” Giunta says. “The next important thing in communication is validation.”

If somebody says they lost a bag, don’t argue with them. It’s better to validate. But one can also use redirection and shift the conversation.

Giunta says, “Sometimes that simple connection of the past, if you can bring it to them in the moment, can help you go to another track. If you’re on a train that’s going to crash, pull the emergency switch and find another track.”

The train, though, isn’t always the person with dementia. Sometimes caregivers and providers can be the ones who cause the crash.

“Sometimes that train that’s going to crash is not them,” Giunta says. “It’s you.”

She talks about her “Alzheimer’s arsenal,” an imaginary backpack filled with tools.

“I know Mary is someone who likes chocolate,” Giunta says. “I get chocolate if she can have it.”

“If you have heard the patient’s Elvis story 16 times, you might want to ask about that time at the U.N. instead,” Giunta continues.

Describing the impersonal nature of so much care, she notes, “In a healthcare professional world people are in and out of the room so quickly. They don’t have time to get to know Mary.”

In order to prevent agitation, providers may want to talk with caregivers, find out what a person can hear and what types of communication are either effective or unsettling.

“They may like small, bite-sized pieces,” Giunta adds. “In the beginning, you don’t know what you don’t know.”

Virtual training in which people find out what it feels like to have dementia can help. They wear orthotics in shoes to simulate neuropathy, objects on their hands to affect motor control, glasses to limit peripheral vision and head phones filled with noise.

“Their brain doesn’t process as quickly as ours,” Giunta notes. “When they hear noise, they may not move on.”

Just as you would when speaking with someone of limited English proficiency, make sure you correct your approach, make eye contact, keep statements to one task or question at a time and talk slowly and clearly. “Look for the acknowledgement before going on,” Giunta advises. “Slow down and make sure each thing being said is acknowledged by the person with whom you’re speaking.”

She says best practices including paying attention to the caregiver and respecting the patient. “Don’t speak only to the caregiver in front of the patient,” Giunta says. “Speak to the caregiver without the patient present.”

LGBTQ

LGBTQ individuals face hurdles in society and in the healthcare system, yet hospitals and providers often lack data on sexual orientation and gender identity. The reason is simple: intake paperwork often does not address these aspects of identity. Statistics indicate that there is a lack of LGBTQ cultural competence in healthcare.

“LGBTQ individuals are less likely than their heterosexual peers to reach out to providers because they fear orientation- or gender-biased discrimination and harassment,” says LGBTQ advocate and conference co-chair Alyssa Cottone.

About 16 percent of LGBTQ Americans surveyed said they were discriminated against by doctors or in healthcare – the same percentage who said that happened while dealing with police, according to a Harvard/NPR/Robert Wood Johnson study. While it may be shocking that the LGBTQ population believes hostility or ignorance among providers is as widespread among police, statistics tell us that is the perception and possibly the case.

There is a lot of diversity in terms of policies, culture and welcoming attitude toward LGBTQ patients. But large systems often are less flexible, according to one conference attendee representing this group.

according to one conference attendee representing this group.

“It tends to be individual health and wellness providers who are more open,” one trans person says. “I found an electrolysis [provider] that advertised they are LGBTQ-friendly. I don’t think you see that as much in the healthcare industry as the wellness industry.”

Healthcare forms rarely collect data related to sexual orientation and even then, often focus only on binary choices. The trans patient sought to transform a doctor’s practice, indicating that proper information is what is at stake here, not privacy.

A trans patient says, “I tried to get them to become more trans-friendly, to point out they’ll make more money. They’ll attract patients they wouldn’t be able to attract otherwise. I couldn’t get the real higher-ups to hear that.”

It’s important for providers to be aware that some in this group may have been rejected at home. Wyatt talks about a gay black man who was rejected by his family. “They were a prominent black family,” Wyatt says of this example from the past. “Think about the early Fifties and Sixties.”

This rejection ended his family’s ability to be a support network. “He felt totally rejected,” Wyatt says. “He went a decade without going home.”

He found his network at college and moved to New York City. Providers need to be aware of the presence or absence of a family support network.

The United States faces issues, but in some Middle Eastern countries, LGBTQ people sometimes are seen as bringing dishonor on their family — and sometimes “disappear.”

“They will put you in a facility and basically keep you under watch,” Wyatt says of some nations. “It’s a global issue.”

Still, the argument that things are better here is a weak response to problems. Improving intake, gathering data and listening to the LGBTQ population can improve care and cultural competency. Often something as simple as hearing concerns can help us improve care. But we have to be willing to absorb new information and change, even if that can mean modifying protocols for certain populations.

LGBTQ and Language

“In Pittsburgh, there is a ‘Dignity and Respect’ campaign designed to promote respect for self, others and the community,” says Alyssa Cottone. While that refers to the way we deal with each other, language plays a major role in the way we interact. And for the LGBTQ community, that means using language in ways with which they are comfortable.

In one example, “sexual orientation” is viewed as more appropriate than “sexual preference”. It isn’t, though, just about words, but about the way sexuality is perceived.

“When I think of ‘prefer,’ I think I’m on lunch break. Do I prefer Chipotle or sushi? I have a choice,” Cottone says. “For people who identify as LGBTQ, there’s no choice or preference.”

She says the wrong words “can be a slap in the face.” And she’s seen the shift from “preference” to “orientation”.

“We’ve steered away from using sexual preference,” Cottone says. “Sexual orientation is where you want to be. It’s capturing whom someone is physically attracted to.”

Sexual orientation and sexual behavior can be different from gender identity. A person can identify as transgender regardless of orientation. Forms should refer to the gender with which people identify themselves, and that can include non-binary choices and biological sex.

“Language is huge. Sexual orientation versus sexual preference is one way to promote a safe space,” Cottone says. “We need to create safe spaces that say, ‘It’s OK to tell me that you’re transgender. I want to best serve you.’”

Language often reflects other issues as well. In an OB/Gyn office, a doctor asks about a pregnant woman’s husband, assuming the patient is married to a man.

“It just means they’re not culturally competent,” Cottone says. “They’re not using terms that say to a lesbian, ‘You’re good here. Not all women are married to men.’”

Becoming aware of assumptions is a crucial step in providing better care. Someone who assumes a Hispanic person works in a specific profession or that the person accompanying a patient is a caregiver is plagued by assumptions that in fact are another kind of prejudice. Paperwork sometimes reflects assumptions. While some might think paperwork indicating sexual preference and not orientation is a detail, Cottone disagrees.

“It is a big deal. To say that it’s a choice doesn’t make sense. It could be intimidating,” she says. “Educate yourself. Reach out to your local LGBTQ organization. If you’re a provider, have a training.”

The Platinum Rule

We’ve all heard of and been brought up with the golden rule: Treat others the way you’d like to be treated. In dealing with vulnerable populations, such as LGBTQ, though, this rule may not be the best approach.

“The golden rule is ‘treat others the way you want them to treat you’,” Cottone says. “I propose to you the platinum rule, which is: Treat others the way they want to be treated.”

Providers can talk with people in vulnerable populations, such as those who are LGBTQ, to find out what they prefer. Friends and loved ones can give guidance. But for healthcare, this can also mean having providers from various groups and having people from various groups depicted in healthcare materials.

“More people are coming out. They need to be represented in the collateral in the offices they go to. Be sensitive. If you don’t know, say you don’t know,” Cottone says. “I’m unsure of your health disparities. I’ll do my best to learn.”

This type of thinking, applying the platinum rule, can extend far beyond LGBTQ.

“If it’s one population we’re not being sensitive to, we’re running the risk of not being sensitive to many populations,” Cottone adds.

Improper information can actually lead to improper care. A trans person with ovaries may present as a man, but have ruptured ovaries.

“You won’t know that, if it’s not on your paperwork,” Cottone says. “The OB/GYN may not know the person is a trans man with ovaries.”

Seeking healthcare can be traumatic for people who are medically misunderstood. This can add to stress.

“There are high suicide rates among this population,” Cottone says. “It’s something we need to take seriously.”

When someone is misunderstood or hurt by someone they go to for help, that can be traumatic. Healthcare systems need to welcome everyone. Even the name a provider calls someone can matter a great deal. Passports can have “Also Known As.” Bob may want to be called Sandy: Documents can say the legal name is “Bob also known as Sandy.”

“Some of us prefer a nickname,” Cottone says. “What’s the difference between a nickname and a preferred name?”

English Not Spoken

Dr. Ronald Wyatt speaks one language to fellow physicians and another to patients in his home state of Alabama.

“When I’m in practice, I ‘speak medicine’ with my colleagues,” Wyatt says. “When I was in practice in Alabama, I spoke four different languages.”

Wyatt talks about how he heard about giving a patient “life water” in Alabama. That meant giving someone IV fluid.

“It’s a different language. Northeast, Northwest Alabama, Southeast Alabama. Southwest Alabama,” Wyatt says of regions in the state. “We’re not the same.”

If Alabama has variety, Cook County, in Chicago, is a microcosm of the world. “English, Spanish and Polish, there are more than 100 languages spoken by the workforce and patients in the Cook County Health system,” Wyatt adds. “They bring their lives with them from all over the world. They don’t speak the language. But they come for the care.”

People who speak little English face additional problems in the workplace, daily life and the healthcare system. Language barriers can prevent  providers from getting the accurate information they need to provide treatment. Road blocks removed mean open roads. But we have to recognize they are in front of us, and take action.

providers from getting the accurate information they need to provide treatment. Road blocks removed mean open roads. But we have to recognize they are in front of us, and take action.

“Nodding and not understanding what’s going on, especially in a healthcare setting, can be dangerous,” one provider says.

Another provider talks about a patient whom others assumed was speaking Spanish. She soon figured out he was from British Guyana: He was actually speaking English, although others had been speaking Spanish to him, assuming he understood.

“No one understood him. He was speaking what you would call pidgin English or creole,” a registered nurse, says. “They were communicating to him in Spanish. He had no idea what they were saying to him.”

The nurse also remembers a patient who smiled and nodded – and spoke Spanish.

“No one ever bothered to explain to him or speak to him in Spanish,” she says. “That was his primary language. When I took the literature to him in Spanish, I saw the way he lit up. English was not his primary language.”

Some patients will not indicate on forms that a language other than English is their preferred language. In some cases, however, they still prefer the foreign language.

“A lot of people if you ask them, don’t want to say they speak another language,” a nurse says, “They feel it’s a stereotype.”

Sometimes, however, people do want to be spoken to in English, even if it’s not their native tongue. A nurse recently had a patient from Pakistan who spoke Urdu. “I wanted to speak to her in Urdu,” the nurse says. “She said, ‘No, I speak English.’” Assumptions are the enemy of accuracy.

It’s sometimes possible to provide caregivers who speak the patient’s language. But that’s not always the case.

“I’m seeing people call and say, ‘I want a caregiver who speaks my language.’ That can be difficult to do,” Cottone says. “They may want a specific type of caregiver or one with a specific background, training or skill sets.”

Patrick Samedy says language needs to be a bridge, not a barrier. Interpreters can become a crucial link in the relationship between patient and provider.

“LEP patients are safer and have fewer readmissions with professional interpreters,” he says.

Families that don’t speak English have the standard problems that go with limited English proficiency. But these are compounded when you throw children into the mix. Mirna Cortes-Obers saw examples when she worked as a health advocate with the New York Immigration Coalition. She remembers a mother who took her 15-year-old son to see a psychiatrist at a community mental health center.

The mother, who spoke Spanish and had very limited English proficiency, wasn’t asked in which language she was most comfortable. She soon received paperwork in the mail to be filled out, including a form requesting her son’s medical history, written in English only.

“A bilingual social worker from a different agency, who happened to visit the family at their home, translated the form for her,” Cortes-Obers says.

For nearly a year, the clinic did not provide her with free mandated language assistance services, Cortes-Obers says. As a result, she couldn’t talk with the psychiatrist, providing information and assisting in care.

“The mother was frustrated when she heard her son telling the psychiatrist that everything was okay, even though she did not believe this was true,” Cortes-Obers adds. “Unfortunately, the psychiatrist had only communicated with the son, and had totally depended on a minor child for information.”

Just as providers can get additional information from a caregiver for someone with dementia, they can get information from a parent.

“She wasn’t able to tell the psychiatrist that her son was aggressive, breaking things and not sleeping well,” Cortes-Obers says, “and that she believed the medication was not working.”

She eventually was given language assistance, enabling her to be involved in her son’s treatment, Cortes-Obers explains. But the delay points to the problem when there is a language barrier, locking a parent out of a process. Even if the psychiatrist could speak English with the son, the language barrier, in this case, came into play with a parent.

Breaking through the Language Barrier

Kayla, who has worked with AmeriCorps, says it’s possible to get translators and certified interpreter services in person or remotely. And phone systems can operate in the most widely spoken languages. According to dementia specialist Laura Giunta, translators can “combat” misunderstanding and confusion.

Moulder says staff who speak various languages can help, but matching that person to the patient isn’t always easy. Providers may sometimes use family members as translators, but that’s not the best route.

“If I need to schedule someone who speaks Cantonese, it’s a challenge,” Moulder says. “You can schedule a certified medical interpreter. You don’t necessarily want to use a family member. You have to be certain that what the provider is saying is accurately translated and the answers are truthfully coming.”

Even when English is spoken, sometimes information is not provided. When providers list medications, they may not explain the dangers, possibly contributing to the current opioid epidemic. Simply listing information that is not understood may liberate a provider, making the person feel they fulfilled an obligation. But facts not understood might as well be facts not provided. Language is information. And when there are language or information barriers, consequences ensue.

Recruiting and relying on nurses from other nations to supplement the workforce can help provide care. But language can have other impacts. Many nurses from the Philippines, for instance, work in the United States and other nations. Hospitals in Qatar, Wyatt says, employ thousands of nurses from the Philippines.

“We would do these simulations and observe them,” says Ronald Wyatt. “When nurses are in a stressful setting, they resort to their native language. The patient’s there in the middle.”

An action that can provide comfort to the provider — reverting to a native language — can produce discomfort among those receiving care. Body language matters as well. A skittish or prejudiced provider may communicate discomfort silently. We must be aware of the silent language we all speak, either setting patients at ease or setting off silent alarms.

“It’s body language, how words are spoken,” Wyatt says. “Linguistics impact patient safety.”

Communication has long been an issue in healthcare, and lies at the heart of some problems. Hospitals are trying to change the culture, so providers communicate better with each other – and with patients. Many hospitals have adopted a system used in aviation, encouraging all workers to raise any issues.

In the past, a nurse might be afraid to overstep her or his authority by raising a concern in the operating room. Many hospitals these days encourage this through a “flatter” hierarchy. We also need to be sure that we encourage patients to be part of this flat hierarchy – and not put them down, making them afraid of the doctor’s authority.

Both Sides Now

Healthcare providers sometimes learn more about the system from being a patient themselves than from years as a provider. As part of his job, Kyle Schuessler routinely prepared patients in emergency rooms for EKGs. It was a simple process. He gave women a gown for modesty and stepped out of the room. Men were simply told to remove their shirts and change. At first glance, these processes appeared acceptable. But after his own transition from female to male, he needed a cardiogram himself.

“It opened my eyes to how differently we treat patients based on ,” he continues. “And she got my cardiogram done. It was in that exam room that I realized how differently we treated men and women.”

“It opened my eyes to how differently we treat patients based on ,” he continues. “And she got my cardiogram done. It was in that exam room that I realized how differently we treated men and women.”

Schuessler concluded that the assumption that men would be comfortable removing their shirt might be wrong. Some might like a gown. “Men may not want to expose their chest. It’s cold. They’re uncomfortable. They feel too fat, too thin, or hairy or not hairy enough,” Schuessler says. “Or they may have an embarrassing tattoo.”

While Schuessler faced an uncomfortable situation, it led to a change in approach, following the platinum rule, giving all people the option of a gown.

“In that moment, I changed my process at work when I do a cardiogram,” Schuessler says. “Every patient is offered a gown and given privacy when they change.”

Prejudice and the Patient